Prior to the abundant use of concrete as the standard material, curbs were made of local quarried or other mined stone materials. Granite, such as seen above, made an excellent (although expensive) material for curbing, as its hardened nature reduced its overall susceptibility to erosion and damage from street activities (e.g. cart and horse traffic, non-inflatable wheels, pedestrians). Its weight and density also were an advantage over softer stones as it made a rigid edge that was easy to clean and hard to move or steal.

Photo rackcdn.com

Before anyone is lost to their thoughts or misgivings about the title of this post, this is not a piece on Germany in World War II or military strategies. Rather, this is about how odd parallels can be drawn between streets and nature, the built environment and natural one, and how an understanding of history may aid in creating new stormwater strategies for innovative functions.

But, before we rise to the curb cut (or recess to the street), it is paramount to first understand the history of the battlefield between stormwater and waste management in street design, using the United States as a case study.

The Co-Evolution of Streets and Waste in the United States

Streets have been significant design elements throughout most major civilizations, providing easier passage of goods and services to and from remote areas and larger population centers. Their texture has varied, but their function has remained the same: collection and movement. Whether it is modern movement of vehicles and people from place to place on a daily commute or a historic gathering of everything thrown out with the wash water (literally) in 1800’s New York City, streets are never still.

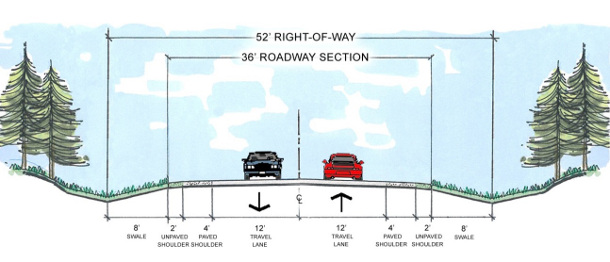

Street design in the United States prior to the Industrial Revolution tended to be what is referred to as the rural road design, or a curb-less section, as seen in the image below. These simple roads were inexpensive to design and construct, a could be made with any type of surface materials (e.g. grass, gravel, asphalt) and lots of space. Because the swales that flanked the edge of these roads needed to remove all the water from the road surface itself, they tend to be wider than roads with curbs. Still common today in many rural and suburban areas, these roads are generally designed to have the high point located in the center of the road, and the water that falls on the road sheets to the sides and off into the adjacent ditches so as not to interfere with the movement of traffic.

A typical rural road cross-section, with its composite features: crowned road surface and shoulders to move water efficiently to the swales or ditches for water transfer and/or storage. With this configuration, unless the ditches are filled to capacity and water is not able to be moved away (conveyed) quickly enough, water rarely ponds on the road surface, affecting the flow of traffic. As compared to urban sections, these roads are inexpensive to construct with no curb and gutter element and no subsurface infrastructure of pipes and sewers.

Photo source: Town of Cary

Water entering the swales was usually delivered to the surrounding pervious landscape for uptake and use. The space and porosity of the adjacent landscape provided a natural means of managing the water on-site, and trees enhanced that processing by capturing and utilizing the water that passed by their roots. Land in these areas was often productive in dairy, animal, and/or crop farming, so people tended to live farther apart, and their overall population densities (people per unit area) were relatively low. Because of these low densities, tax money and relative need for road improvements and maintenance were relatively insignificant compared to the larger cities.

The Industrial Revolution (late 1700s – mid 1800s) in the United States encouraged the movement of vast numbers of people into larger cities like New York and Philadelphia to work in factory jobs and take advantage of the promise of a better life. Conversion of animal-powered machinery to fuel-powered machinery and factories created a demand for workers. Urban populations soared, and there were often shortages of housing to accommodate all the newcomers. In order to accommodate the large number of people wanting to live and work in the same place, higher density housing in multi-story, multiple-unit structures was built along an organized street grid.

During this period of rapid industrialization, the streets were designed and constructed to move all types of waste (human, garbage, environmental, etc.) away from dwellings. There were few indoor bathrooms and, with no municipal sanitation efforts and no sewer system, often the street served as the only waste collection “system.” Waste of all types simply sat in the streets with nowhere to go – until it rained. Then streets would become massive conveyances for garbage, soil, microbes, and other debris, seeping back in to homes and infecting wells and other water sources along the way.

Children play in the gutters next to a horse carcass in this powerful photo taken in New York City, NY, in 1900. The gutters and the cobblestone street surface are separated by a collection channel, shown at the children’s feet, for collecting and conveying dirt, debris, stormwater, and other cast off waste in lieu of a municipal sanitation system at this point in history.

Photo Source: Ephemeral New York

In short, waste was in excess of the infrastructure and technology of the time, and as a result, disease ran rampant in the streets. Sanitation standards and disease reduction had not been operationalized by cities, nor did people understand that poor waste sanitation could lead to the rapid communication of disease. It was not until the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak in the Soho District of London that this link was made directly. The majority of Soho dwellings commonly had individual cesspools to collect waste dug under the lowest floors. When the cesspools filled up – which happened quickly – people simply threw waste in the nearby Thames River, effectively adopting the contemporary joke, “the solution to pollution is dilution.” Cholera ran rampant on Broad Street in 1954, and by the end of the outbreak, 616 deaths had occurred due to this bacteria. During this time, John Snow and Reverend Henry Whitehead studied the geographic pattern of the incidences of reported cases and found an alarming pattern correlating those that took their water from the Broad Street pump with the cases of illness. A nearby abandoned, leaky cesspit was later attributed with both those deaths. The awareness of the link between waste and disease led to foundations of epidemiology and modern municipal waste treatment.

It was the end of the 1800s before waste management was addressed at the city level. G.E. Louis writes about the evolution of waste management being a slow process due to a lag in knowledge and funding:

American cities lacked organized public works for street cleaning, refuse collection, water treatment, and human waste removal until the early 1800s. Recurrent epidemics forced efforts to improve public health and the environment. The belief in anticontagionism led to the construction of water treatment and sewerage works during the nineteenth century, by sanitary engineers working for regional public health authorities. This infrastructure was capital intensive and required regional institutions to finance and administer it. By the time attention turned to solid waste management in the 1880s, funding was not available for a regional infrastructure. Thus, solid waste management was established as a local responsibility, centered on nearby municipal dumps.(Louis, 2004)

The volume of waste was a huge problem, but an even bigger problem was inadequate and disorganized disposal. One simple, inexpensive solution to protect people from disease communication was to prevent the water and waste in the streets from returning to the people within their dwellings. The simple device that wielded so much power to hold back the filth was the curb.

A simple design for a powerful use, the modern curb serves as separation of pedestrians from vehicles, people from water and waste, upland from lowland, and public from private. The movement of waste to the edges from the adjacent sidewalk and roadway is visible in the collection of leaves and debris in the gutter.

Photo Source: Wikipedia

Curbs functioned to separate streets from people, and waste from health. Often up to a foot or more in height, these barriers were a simple method of waste containment. As each rain event occurred, curbs prevent contaminated street water from re-entering the relatively clean surrounding areas, in the same way the banks of a channel serve to contain and direct the flow of a stream. But unlike streams, these hardened barriers were designed to accept but not release any waste or water that entered their flowage.

Things have changed since the 1800s, thankfully. Sewers are now common utilities within most developed areas. In most cases today, we see the separation of storm sewers and sanitary (waste) sewers at the municipal level (MS4s). But throughout all this, we still see that reinforcing trace of the past flanking the edge of city streets, still containing and conveying the water and making the passage of people and vehicles a bit safer on the sidewalks above than the streets below by containing and keeping the water and the waste at bay.

Andrea Wedul is a Graduate Landscape Architect with The Kestrel Design Group.

Sources Cited

Louis, G. E. (2004, August). A historical context of municipal solid waste management in the United States. Waste Management and Research (via PubMed.gov), 4, 306-322.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. Retrieved April 13, 2013, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1854_Broad_Street_cholera_outbreak